YLE News: Halloween Candy - A Smart Guide for Parents

|

Keeping up with public health developments—both policy and health events—is like drinking from a firehose these days. YLE content is free, but we need financial support to keep the team sustainable (and sane). If you can, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription below.

Halloween candy: A smart guide for parents

How to enjoy Halloween without letting sugar or falsehoods take over.

|

Happy Halloween! As a mom to two energetic firecrackers, I had four lingering questions for Megan (our YLE Dietitian) as Friday approaches. Her answers were so helpful that I thought you might find them useful too. We had a lot of fun with this post, and I hope it’s helpful for you as the day gets closer.

Does excessive candy actually make my kids insane?

Many of us have witnessed “sugar highs,” but research shows hyperactivity isn’t caused by sugar itself. Scientists have been studying this question for more than a century—since 1922—and the evidence is consistent. When researchers pooled results from 23 studies in a meta-analysis in the 1990s, there was no impact. This is even the case among children who appear sensitive to sugar. A study compared the effects of sugar in children whose parents described them as sensitive to sugar to those who aren’t: there was no difference in behavior, attention, or hyperactivity.

Sugar highs are more likely a combination of the environment and our expectations as parents:

- The setting: Sugary treats often appear at exciting social events where kids are already buzzing with energy, fun, and chaos—not from sugar, but from the moment itself.

- Perception and expectation: While placebo studies found no link between sugar and behavior, they did reveal that parents who believedtheir child had sugar reported more hyperactivity (though they had none). Expectancy bias is powerful, as it shapes what we see.

Should I look out for dyes, like Red Dye #40, in candy?

In short, no.

Artificial food dyes have been making headlines lately, including potential state bans and even FDA actions. From a safety standpoint, these dyes are thoroughly tested and regulated, and global safety limits are set far below what kids typically consume. Some dyes have been shown to cause harm in rats at very high doses—but not in humans at the levels found in candy—and those particular dyes (like Red Dye #3) are being banned from the market. Contrary to popular belief, though, the majority of dyes currently used in the U.S. (like Red Dye #40) are also permitted in Europe, where regulators take an even more cautious, hazard-based approach to food safety. They simply appear under different names on European food labels.

The bigger issue isn’t the dyes themselves, but the colorful, highly processed foods they’re often found in—usually high in sugar and low in nutrients. That’s something to think about for everyday diets, not for occasional treats like Halloween or holidays. Personally, I’d worry more about a stomachache from too much sugar than from the colors themselves.

In case you missed it, here is some more information on dyes previously covered in YLE:

What’s the most dangerous thing about Halloween?

Candy tampering is an urban legend, usually borne of a genuine parental fear that children might get something from a stranger, and/or stemming from falsehoods taken out of context. For example, in 2022, the DEA issued a warning about brightly colored fentanyl—“rainbow fentanyl”—which can appear as pills, powder, or blocks resembling candy or sidewalk chalk. The alert, released in August, was unrelated to Halloween, but it fueled widespread fears that persisted through the holiday season.

(Note: The YLE team checked what’s circulating on social media today, and there doesn’t seem to be many specific rumors this year, which is great news.)

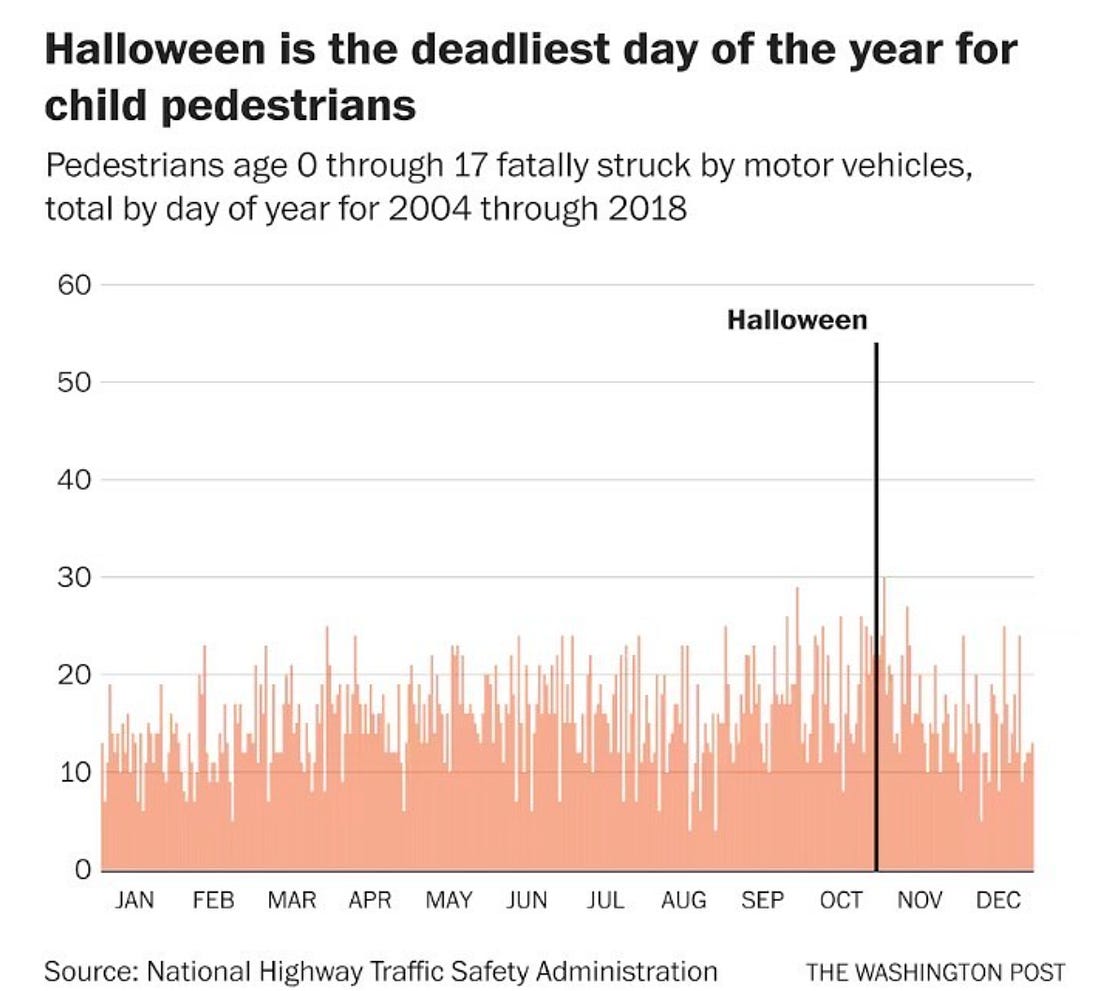

The biggest and most unusual spike we see around Halloween is in pedestrian accidents, particularly child pedestrian deaths, which consistently rise on this day, even though they remain rare.

Studies have shown that the risk of pedestrian deaths on Halloween doesn’t change based on the child’s sex, the decade of Halloween, whether Halloween is on a weekend or a weekday, rural vs. urban, or region in the United States. The story stays the same: Kids ages 4-8 are at the highest risk during Halloween, followed by 9-12 year olds and 13-17 year olds.

How do I handle all the candy?

Balance the celebratory spirit of Halloween with healthy moderation. Here are a few ways to do that:

Before Halloween

- Have a game plan. A little planning can help parents feel more prepared, confident, and consistent.

- Keep candy in perspective. If we make it a big deal, it becomes a big deal. Every child responds differently to food, so use your best judgment and trust your gut.

- For toddlers under two, try to avoid candy. Dietary Guidelines recommend no added sugar until age two, since this is an important window when taste preferences are developing. For kids under five, also be mindful of choking hazards (hard candies, caramels, and gummies).

Halloween Night

- Serve a balanced meal before heading out. Getting some good nutrition in their bellies can help fuel a fun evening and prevent hungry trick-or-treating.

- Let your kids take the lead. Allow them to pick and eat the candy they want. They may overdo it. They may not. Try not to interfere too much if you can help it.

- Make it fun. Sort it, trade it, talk about the ones you love (and the ones you don’t).

After Halloween

- Keep candy in a central, shared location, such as the kitchen or pantry. Be mindful of storing in places out of reach from pets (chocolate and sugar-free candies) and young children (choking hazards).

- Set gentle boundaries. For example, let them choose one or two pieces to have with dinner or to pack in their lunch.

- Have calm responses ready for pushback. Try: “Let’s give our bellies a break for now, how about picking one for your lunchbox?” or “That’s not on the menu right now, but [safe, enjoyed food] is!” (Jill Castle has great resources on this topic, too.)

- I also like asking my kids what happened to the Hungry Caterpillar after eating too many treats. It makes the point in a silly, memorable way.

- Downsize when the novelty fades. After about a week, interest usually wanes. You can move favorites to the freezer, donate some, bring a stash to work, or try techniques like the Switch Witch. This helps kids and parents transition from the daily candy habit.

At the end of the day, a short break from “healthy eating” is much easier to recover from than risking your child’s relationship with food. Remember: foods vary in nutritional value, but they hold no moral value—they’re not good, bad, clean, or dirty, and they certainly don’t reflect your worth as a parent.

Bottom line

Childhood is painfully short. Let’s keep the magic of Halloween alive without letting sugar or guilt haunt us.

Happy Halloween!

Love, Megan

Megan Maisano, MS, RDN, is a Registered Dietitian Nutritionist. She holds a BS in psychology from the United States Military Academy at West Point and an MS in nutrition communications and behavior change from the Friedman School of Nutrition at Tufts University. During the day, Megan works at National Dairy Council, a non-profit dairy nutrition research and education organization. (She does not write about the dairy industry for YLE.) Megan is a lifelong learner of all things food, health, and well-being and believes “wellness” is deeply personal and should help us feel nourished and empowered, never restricted or discouraged.

Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE) is founded and operated by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. YLE is a public health newsletter that reaches over 390,000 people in more than 132 countries, with one goal: to translate the ever-evolving public health science so that people are well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions.